The world's youngest country is going through puberty

South Sudan - Why freedom fighters can't be nation builders and ever-hopeful youth movements should have our attention.

Fifteen years into its independence from the north, some say a new civil war is imminent in South Sudan. Hopes among the people of the world’s youngest country are that the 2018 peace agreement will finally be implemented. Instead, in the country’s Upper Nile, bullets are flying again. Eternal rivals, President Kiir and First Vice President Machar are once again embroiled in a dispute. It shows similarities to when I visited South Sudan back in 2018. Let me tell you what that trip taught me about nation building and the country’s ever-promising youth.

Before we embark on this journey to Togo, I’d like to let you know that my book - Het continent van de toekomst (The Continent of the Future) - will hit the shelves soon. It is an atypical travel book (in Dutch, for now) about sixteen countries, seen through the eyes of Africans in their twenties and thirties. It is already available for pre-order here.

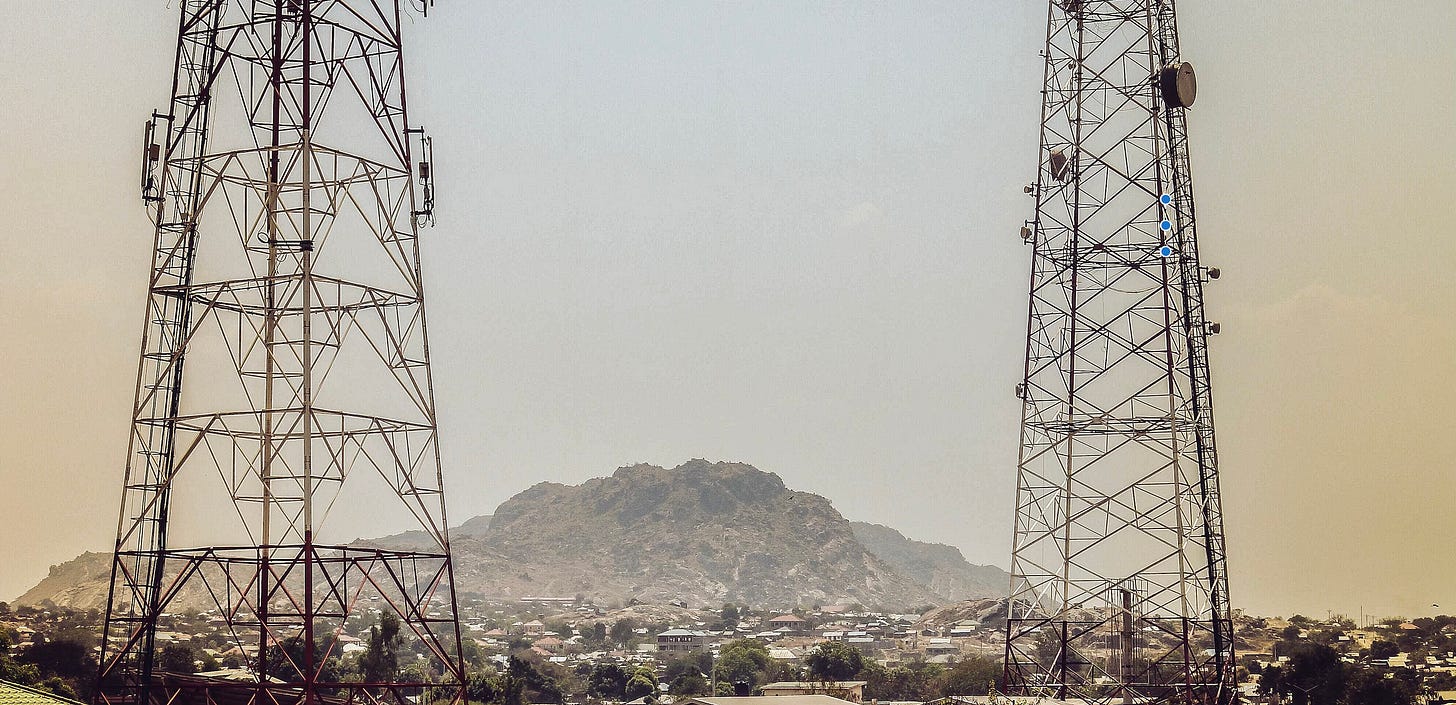

South Sudan - When leaving the airport in Juba, the South Sudanese capital, the air felt heavy. The streets were filled with uncertainties en ruins of recent fighting. While waiting in line at border security, I was invited to a get together at a hotel rooftop, scheduled for that evening. Although I was well aware that South Sudan, in many ways, is an untamed expanse of land, governed by immature leaders who wield little authority, I didn’t expect that it would draw such a curious crowd.

The terrace was a catch-all for a nation still searching for its place on this planet. After a turbulent week, the weekend was ushered in with heavy drinking and a panoramic view of the city.

I met with Western aid workers and solitary missionaries, their rumpled vests hanging loose like a second skin, drawn to the country like bees to honey. After all—whether in the name of Jesus or otherwise—there were many souls to be won. I saw local opportunists, draped in designer clothes and jewelry, their luxuries bought with dubious wealth, while they cozied up to the South Sudanese elite. I toasted with European diplomats, exchanged words with cunning businessmen, and shook hands with (what later appeared to be) an Israeli arms dealer. Meanwhile, a former child soldier that was appointed to me for security reasons, stood guard by my car. It felt as if I entered the set of a mediocre action movie and it made me wonder how South Sudan could ever move into the future like this.

At the same time, the country's magnetic pull—drawing in both humanitarian adventurers and criminal opportunists—is no mystery, nor are its unchecked growing pains or corrupted politics. When one looks back at South Sudan’s tumultuous history, its present-day struggles seem almost inevitable.

The nation's complexity is rooted in the long-standing discord between northern and southern Sudan, a divide that stretches back centuries to the days when enslaved Africans from the south were shipped off to the Arab world. Religion deepened the rift: the north predominantly Islamic, the south fertile ground for Christianity. When Sudan broke free from British-Egyptian rule in 1956, the two opposing worlds were forced under one flag, much to the resentment of the southern Sudanese. Under Khartoum’s rule, the south was economically neglected for over half a century, while deprived from its natural resources (oil). And as if that wasn’t enough, a brutal guerrilla war raged between the two regions, carving deep wounds that remain unhealed.

Exhausted by years of fighting, the southern Sudanese finally were allowed to organise a referendum in 2011, where an overwhelming majority voted for independence. On July 9th of that year, the Republic of South Sudan was born. But the euphoria was fleeting. Having broken free from Sudan’s grip, the world’s youngest nation found itself among the poorest, drained and directionless. Inexperienced leaders and a fractured political landscape made stable governance and compromise nearly impossible. President Salva Kiir of the Dinka people, and Vice President Riek Machar, of the Nuer, soon found themselves at irreconcilable odds. Within two years of independence, the country was once again at war.

What followed was a relentless cycle of negotiations, eruptions of violence, and failed peace deals. At last, in 2018, a fragile peace agreement was reached. But the scars of conflict ran deep, current tensions and a possible eruption of violence show.

‘Liberators can never be nation builders,’ Mario explained when I spoke to him in the sweltering heat of a parking lot. The sun seemed to be closer to the earth that day. The warmth pressed every drop of moisture from my body, while we sought shelter in a thin strip of shade.

Mario was the former child soldier who was appointed to me for security reasons, especially in the evening hours. He introduced me to his friends—Mario (the second) and Gabriel. They too once served as child soldiers under a revered general and now found themselves relegated to the back seats of society. All three towered above me, tall and broad-shouldered, but their smiles were shy, their manner timid. They were well aware of the status quo in South Sudan.

According to them, the ongoing tensions were rooted in political mistakes that the liberators made during the independence war against Khartoum, in which factional fighting among the freedom fighters (along ethnic lines and disagreements) caused immense suffering. When South Sudan won its dearly cherished independence, the common enemy vanished—and with it, the fragile threads that had held the nation together. Unity crumbled like dry sand through open fingers. Since then, local disputes have often spiralled into deadly clashes, each one a blow to the delicate balance that keeps the country from tipping once more into chaos.

It has blurred their future, Gabriel explained, as it left a massive burden on the shoulders of the citizens in terms of shattered livelihoods and traumatic memories. At the same time they felt a certain responsibility to help transform the young country into a stable, prosperous and open society that their generation yearns for. Forgiveness was the only way forward according to the three friends. “We’re done with the war, just like everyone else,” Gabriel said calmly. “If Jesus can forgive, then so can we,” Mario added.

The unyielding attitude of the young men was inspiring and restored some faith in a country going through puberty. While directly affected by the dire situation, I met dozens of such young people, similarly urging their leaders to put an end to the cycle of violence.

One of them made me aware of the bullet-riddled walls that were patched up with colorful murals of Anataban (freely translated it means ‘I am tired’). They felt like a weary sigh, a reflection of the tiredness that haunted a next generation. Anataban appeared to be a creative youth movement that calls for integrity, transparency, and justice. At that time, they surreptitiously painted murals that called upon the government and rebels to end the bloodshed.

The collective stands in solidarity with the marginalised. Their campaigns bear no political colours, renounce violence, and place active citizenship at the heart of their mission. To them, respectful collaboration between different ethnic groups is the only way out for a nation in a perpetual state of crisis.

A few days later I was introduced to Manasseh, a musician and the spokesperson of the movement that collaborates with artists, writers and all sorts of change makers. He had a wispy beard, dreadlocks, and a glint of mischief in his eyes—I remember he brought to mind a young Bob Marley. With a deep voice and deliberate stride, he spoke of how South Sudanese have learned to embrace their suffering, finding a strange sort of familiarity in it. It was his way of acknowledging the weight of his homeland’s troubles, while simultaneously emphasizing the quiet strength of the population.

"Anataban holds its leaders accountable and demands improvement, but our main focus is on uniting South Sudan." Manasseh emphasized that reconciliation is the key to a stable society where national agreements take precedence over local disputes. He refrained from making any predictions about the future of his country and explained that the South Sudanese wheel had to be invented first, before the cart could start moving.

At times, Anataban’s campaigns succeeded. “Initiatives that underscore the importance of a ceasefire and unity, are repeatedly mentioned in peace negotiations.” Additionally, the growing number of young people joining the movement—bringing friends along and launching their own initiatives—instilled confidence. “Young people are bringing different communities together through creativity, like theatre.”

Manasseh emphasized that he and his artistic peers will never lose faith in the youth and firmly reject the notion of a lost generation. On the contrary, they believe that it will be their generation that will carry the nation forward. “As long as our voice is heard and leaders are willing to listen to our ideas.” Believe and ambition, so it seems, gathered momentum among the young, and I can affirm that they’ve never let go of it since.

That’s all for now folks. I hope you’ll stick around and it would be greatly appreciated if you tell friends (to tell friends) about this publication. Feel free to drop me a line in case of any questions or suggestions and don’t forget to have a look at the amazing work of the African creatives I work with here.

Daaf - Writer, traveler and curator for The Bright Continent